Historic Buildings as a Climate Response Tool

Introduction

There is a saying in architecture often repeated: “the greenest building is the one already built.”

While this is a wonderful sentiment, it fails to mention the often-complex interplay between repurposing existing building stock and cultural heritage, and the intricacies necessary in renovations to make the kind of sea change needed in the fight against climate change.

Our Director of Sustainability and Building Performance, Z Smith, recently had the pleasure of participating in a webinar with Andrew Potts, of ICOMOS, sponsored by the Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans.

Inspired by and building on several articles that ran in the April article of Preservation in Print, including one with former AIA National board President Carl Elafante, the discussion revolved around how we might use historic buildings as a tool in the fight against climate change?

Of all global industrial CO2 emissions (the kind that influence climate change), 39% come from the building sector. This metric encompasses two facets:

Embodied carbon, or the manufacture, transport and installation of construction materials (which happens up front)

Operational carbon, the building’s energy consumption over time.

In light of this, and New Orleans’ own carbon reduction goal of 50% by the year 2030, what needs to happen? Following is a recap of our conversation exploring some options for intervention. If interested, one can still view the discussion in its entirety via video recording.

A Cultural Context

Fellow participant Andrew Potts first gave some of the policy context behind the climate change issue and discussed how historic preservation and cultural heritage fit into that conversation.

In short, it involves using the power of heritage to drive ambition to decarbonize. This ambition can be served in numerous ways as we adapt historic structures: obviously reusing them in the first place, but making them more efficient, considering recycled materials in renovations, facilitating onsite renewables, and even electrifying (moving from fossil fuels) our historic buildings.

At the same time, we need to build a community’s capacity to work on climate change. The gold standard of climate action in international policy is to look for activities that advance decarbonization while simultaneously advancing other societal benefits—attacking poverty and inequality, progressing sustainable development etc. Cultural values are assets to the community, so strategies that advance the cultural values while advancing the conversation of decarbonization are vital.

We also looked at the issue from an architectural perspective, and how the adaptive reuse of historic buildings can similarly mitigate climate change.

An Architectural Perspective

We started with an example of a project we admire deeply, the Wayne Aspinall Federal Building by Beck Group. A federal building first constructed in 1918, the building has since gone through a deep retrofit that made it not only a more comfortable building, but a net-zero one, meaning the total energy generated onsite equals the energy used on an annual basis.

It’s an example that puts to bed the notion that one can only make net-zero buildings by starting with a clean slate—or ground up construction.

Another wonderful example of sustainable preservation persists in one of the world’s most iconic buildings: The Empire State Building.

The Empire State Building viewed from Rockefeller Center

The Empire State Building, built in the 30s, is a skyscraper with operable windows. It uses less energy per square foot than 80% of all office buildings in America.

While not initially designed for exemplary energy efficiency, today it manages to preserve its architectural character while simultaneously delivering modern levels of comfort with a very small energy footprint.

A little closer to home, we also explored one of EDR’s project at the Elks Building, originally built in 1917, now home to Tulane University’s relocated School of Social Work.

A project that achieved LEED Gold certification, the building now boasts a significantly higher level of comfort for building occupants, along with better daylighting and better views.

It included a completely modern program, in a location that’s especially advantageous for Tulane’s work in the community, given its proximity to neighboring organizations. It also lives on a street with perhaps the highest bus density in New Orleans—a highly accessible building that is similarly an excellent energy, comfort, and air quality performer.

A wonderful clarifying point to make as an argument for these interventions, is that even before we start retrofitting older buildings—because they tend to be built in a time prior to heavy dependence on mechanical heating and cooling—they’re often better baseline performers. A building built in 1920 has a lower energy intensity typically than a building built in 1980, and it’s only when you get to recent construction that they start to do better performance-wise.

A diagram showing energy use intensity across commercial buildings by year of construction.

Moving Beyond Historic Buildings

All said, it’s one thing to talk about historic buildings as a climate response tool. Moving beyond the cherished, it’s crucial to look at those existing buildings outside of historical windows, many built mid-century, and recognize that these too can serve as climate response opportunities for preservation and restoration.

In fact, about half of all commercial buildings were constructed after 1980, and these buildings, while not considered historic by any measure, represent tremendous opportunities for energy efficient interventions.

Case in point, the 1952 SOM Pan American Life building went through numerous incarnations in its lifetime.

Today it is the home for our project with the VA and its New Orleans headquarters building, where all hospital administration and management maintain offices. The building beats the energy code by 22% and is, quite simply, a delightful building to be in.

We can stretch this further beyond mid-century buildings and recognize that unloved buildings constructed fairly recently have a role to play as well. At LWCC, in our work renovating a building first constructed in 1988, we cut its energy use by 2/3.

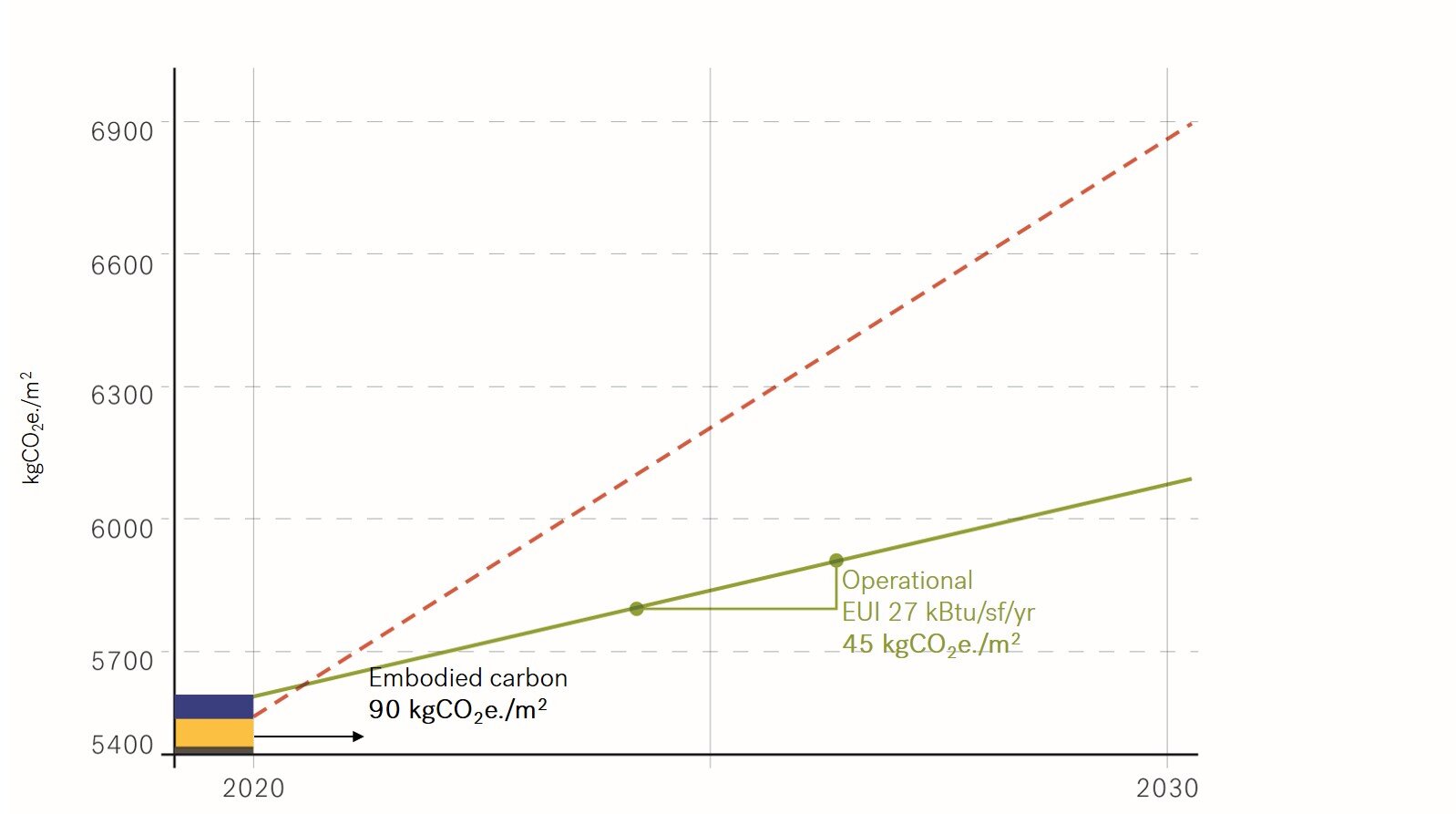

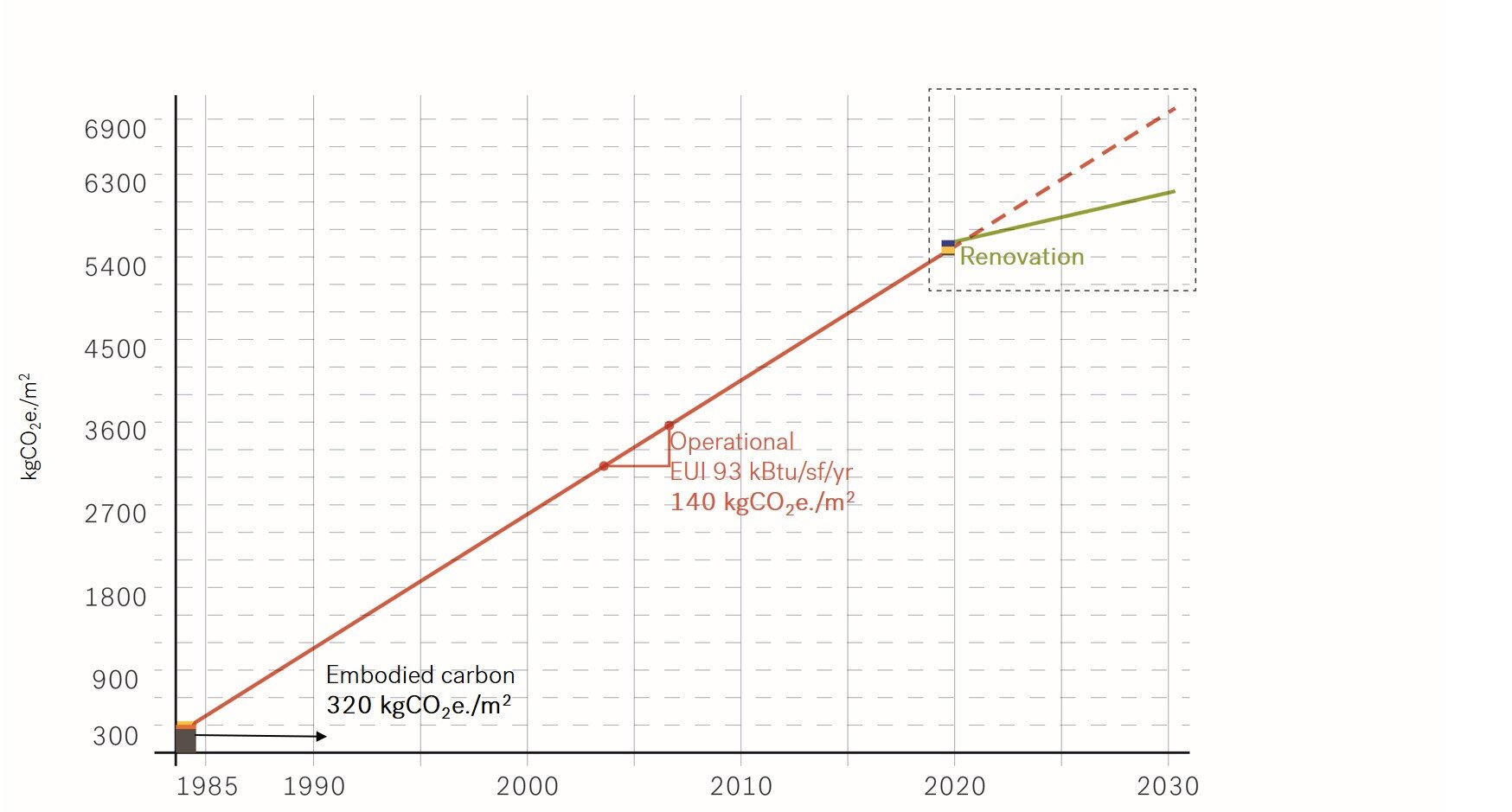

As part of the investigation into the renovation, our Research Fellow Kelsey Wotila did a comparison study on the emissions needed to build a new building for the client versus renovating. What she found is that a tremendous portion of the emissions required for new material construction were allocated to structural requirements. The exterior—all the brick, glass, insulation, roof—and all the things you stick in it, while noticeable, were negligible. In total, the emissions to do a complete gut renovation of the building were paltry when compared to knocking it down and building new.

A comparison of carbon cost between new construction and renovation projects

The other reason to do these kinds of projects lies in the question of comfort. In looking specifically at LWCC’s prior interior, the environment was not a particularly welcoming one—poor daylighting, stale ventilation. In interviewing for the project, we were informed by the client that one of their biggest problems was the discomfort of their employees: they were either too hot or too cold.

Our pitch during the project involved showing them an old data center renovation for Lamar Advertising HQ, where we carved strategic holes, allowing light to penetrate into the middle of the building. We also discussed how other mechanical interventions improved air quality and the environment for occupants and, in the end, this made for a building worth preserving.

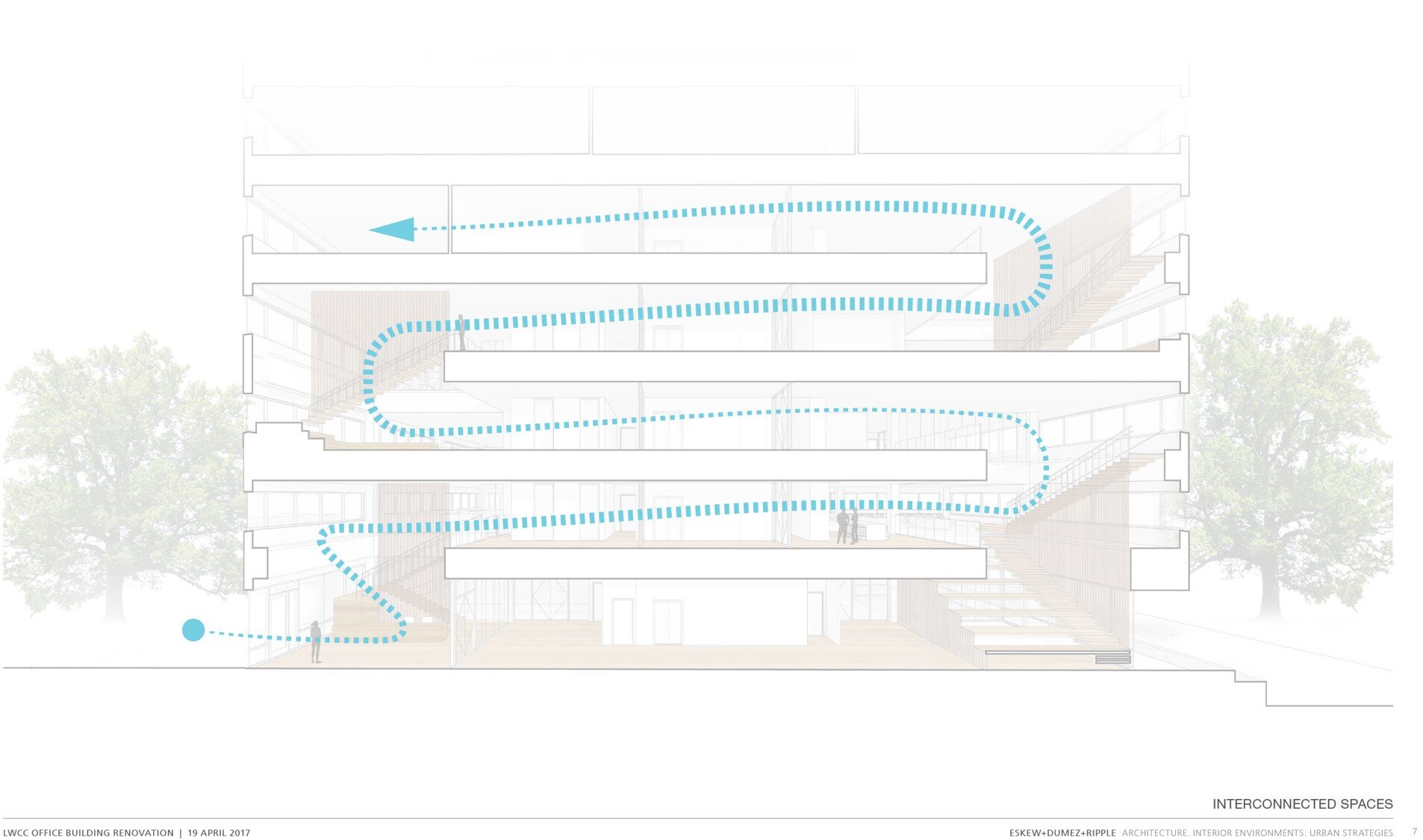

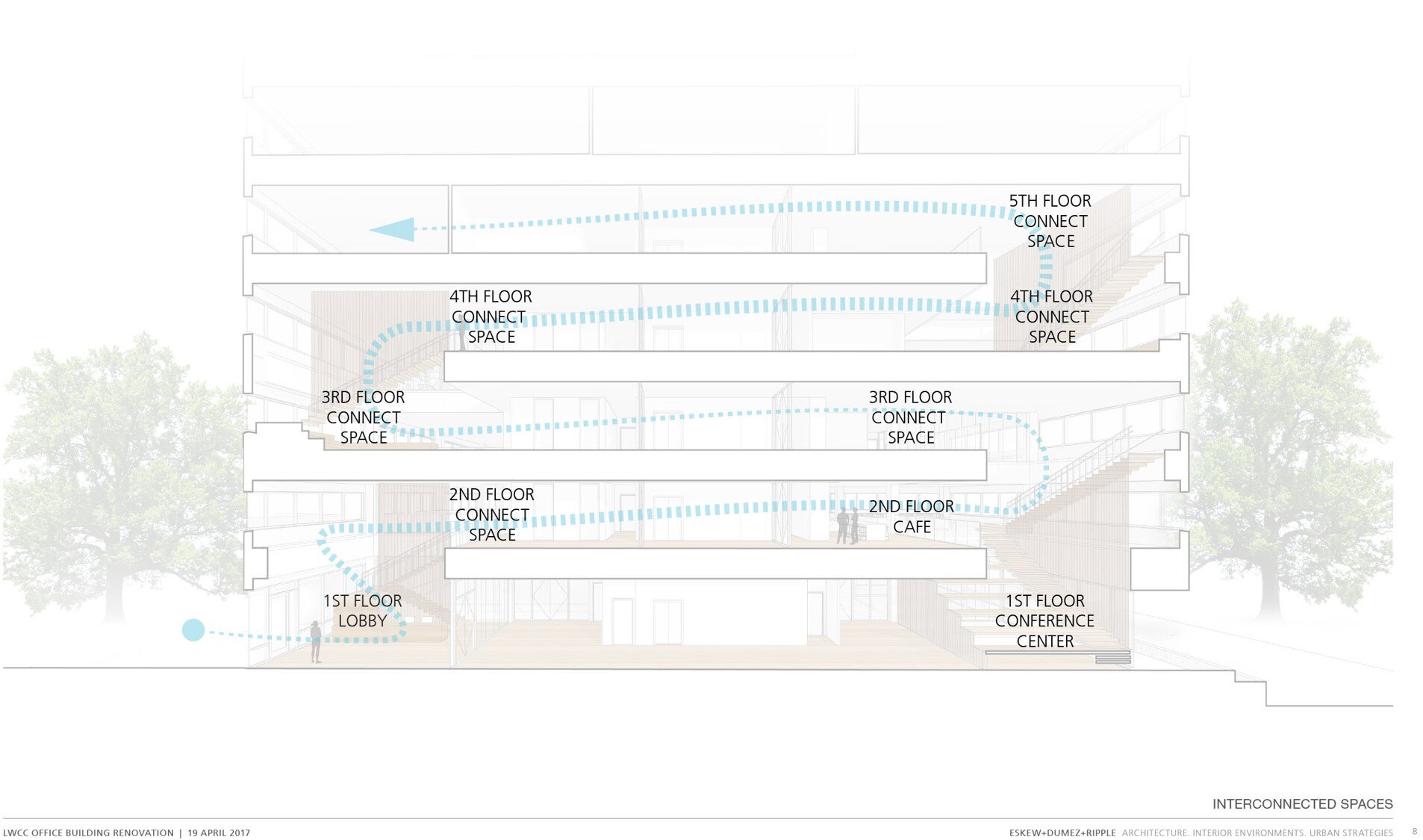

At LWCC, we ultimately accomplished something similar, carving throughout a series of walking paths, that one can use to navigate the building in lieu of elevators and that encourage socialization and casual encounters. What’s truly interesting about the project is that we didn’t touch the building envelope. We altered the interior, carved new holes within, and changed the heating and cooling system.

A diagram of this strategic coring shows how new walking paths were generated throughout the building, promoting opportunities for chance encounters with coworkers, better daylighting, and encouraged activity.

In the end, we looked at both initial carbon of construction and energy moving forward. What the below graph shows is that not only will our intervention pay huge dividends in terms of energy usage moving forward, but equally important, the carbon of construction for the renovation will be paid back in less than one year.

Incredible results can be accomplished across the spectrum, regardless of age.

Making It Personal

Lastly, for those living in older buildings here in New Orleans, there is a similar opportunity to join the fight on an individual basis.

Z himself lives in a shotgun camelback building in New Orleans that without intervention, one might look at as a notoriously poor performer in energy performance. In 2010 his family did a sweeping retrofit, taking it from spending $2500 a year on utilities to $250. They left the exterior largely alone, but fixed the insulation, added solar, added battery storage, and were able to cut energy usage by nearly 90%.'

Z’s historic home in New Orleans, which was retrofitted in 2010, adding solar pattern, an intervention which cut the home’s energy usage by 90%.

Conclusion

The science is settled. We know that carbon emissions are the key contributor in why the planet is changing. Our scientists have made it clear exactly how much carbon we can afford to put in the air. If we want to stay within 1.5 degrees of temperature change, we have a very small drop left in the bucket. In time, at our current rate, this equates to about ten years (which is why people often say we have about ten years to fix our current predicament).

This is sobering news. The silver lining in all of this is that change is possible. That it’s entirely viable to reduce our carbon emissions, and that this change can come in large part from actions taken by architects right now, today. These changes do not have to be mired in existential dilemma, in which we strive to balance environmental responsibility with having a better building. Rather, they can be empowering. There are truly all kinds of co-benefits in making existing buildings better that are worth doing, and that in doing right, will make our planet more hospitable for future generations.