Design Health: Justice in the Built Environment

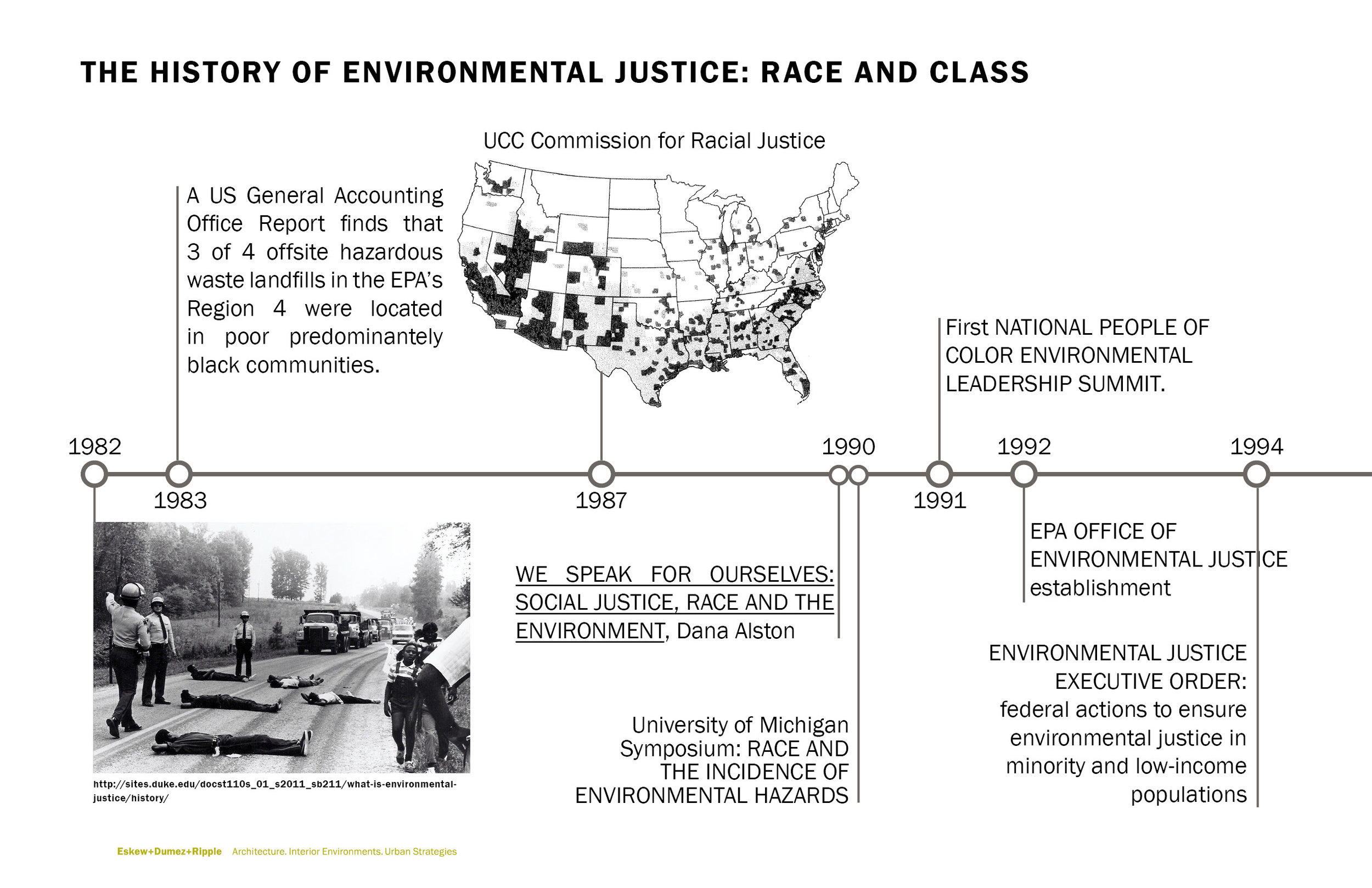

These two images show a small piece from the NOMA presentation I gave last week. The talk related built enviornment improvements to environmental justice concepts and linked the two back to a movement for better health for all through the built environment.

To expand on the first image, the 1982 picture shows protesters lying in front of large trucks carrying PCB contaminated soil to a landfill in Warren County, North Carolina. This story was the spark for the Environmental Justice movement. Here's what happened:

A manufacturer had illegally disposed of large amounts of PCB by a highway. When the state discovered it, they called for the pollution to be gathered and placed in a toxic waste landfill in Warren County, North Carolina. Warren County happened to be a low-income African American community in which many residents owned their own homes. When the residents learned of the plan, they were outraged, deeply concerned about their county becoming a favored dumping ground and fearing water contamination. Eventually the state formed an agreement with the residents, promising that they would not dump anything further on their soil.*

From there studies, conferences and books exploded to understand how race and class were related to environmental issues, and the problem insists until today.

Fear of gentrification is also a rising issue related to the environmental movement. The following pointed quote was disheartening for someone who is interested in environmental improvements.

"Cleanup makes a neighborhood more attractive and may drive up real estate prices, forcing up rents, and thus displacing the populations who suffered the consequences of industrial development, while richer homeowners capture the gains in their property assets."

(Banzhaf and McCormick, 2007)

How do we improve neighborhoods and grow businesses for the local residents instead of displacing them? A "just green enough" method was attempted at the Newton Creek Nature Walk, described by the NY Times as an ironical park that keeps the edges a little rougher. However even this Superfund site seems to be luring developers.

As we see concern about environmental hazards turn into changes in the environment, owners, developers, designers and the public will decide whether all people--and especially those originally inhabiting the place--can benefit from the improvements. If designers and the public change culture such that the built environment is seen as health-impacting (not just "pretty" or a luxury), perhaps the importance of design interventions to human well-being will make good design more widely available for everyone.

Volunteers for America recently opened below market rate housing at Centennial Place, near the old power plant. This project provides housing for lower income peoples in an area that is walkable--or at least bikeable-- to the CBD. The organization's interest in providing healthy housing for residents makes it a perfect case study for the fellowship. The building includes an outdoor courtyard, a rooftop terrace and a community space to socialize residents and give them an appreciation for their location. The insulating windows keep highway and train noise from disturbing the residents. Spaces rented to Boulder Lounge and Fresh Food Factor help to keep the cost of housing down.

As a sort of "developer," this organization is taking the first step into an upcoming market that is sure to become popular for other developers who may try to attract higher income groups. If all goes well, Volunteers for America has now reserved a spot for affordable housing in the area.

*To conclude the story for Warren County: the very next year, water was discovered under the landfill. The concern about water contamination was dead on. It was not until 2003 that the state began actively disposing of the PCB; the soil became safe in 2004.